“Good God! Did we really send men to fight in that?”

4th of August 1914, a bank holiday and someone decided to throw a war.

Field Marshal Douglas Haig, 1st Earl Haig, KT, GCB, OM, GCVO, KCIE was ready. Haig helped organize the British Expeditionary Force (BEF), commanded by Field Marshal Sir John French. That was the John French who the rich son of the Haig Whisky family had lent 2000 guineas to when as fellow officers they served together in the Boer War, because he was about to be bankrupted by poor mining speculations. In case you think Haig was a great friend of his commanding officer he wasn’t. Haig married late and well. His wife, daughter of Baron Vivian Haig was a Lady in Waiting to the Queen so while everyone was getting feisty that summer Haig had been appointed aide-de-camp to King George V. During a royal inspection of Aldershot Haig told the King that he had “grave doubts” about the evenness of French’s temper and military knowledge. He also took potshots at Kitchener and the other leading Generals. Haig was not a fan of artillery but was a big fan of cavalry, so the Expeditionary Force had lots of cavalry horses but not as much in the way of machine guns or cannons.

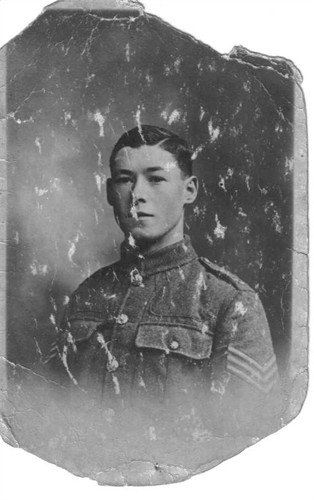

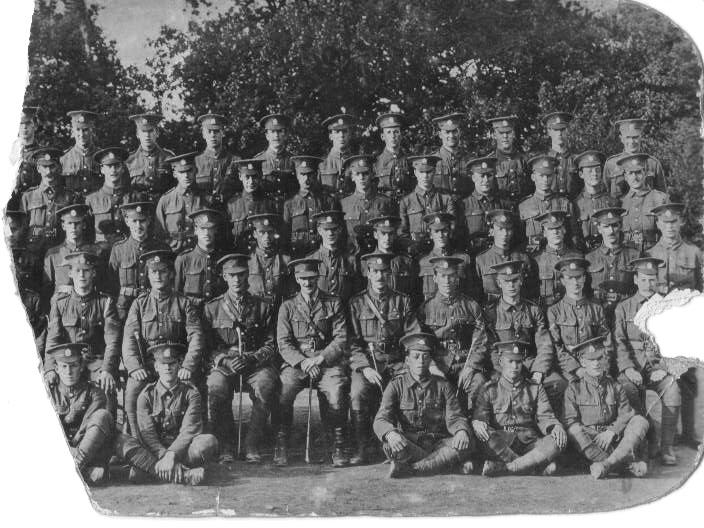

Everyone wanted to do their duty, to do their bit. My Grandfather`s generation all wanted to do their part. Arthur went to Hackney Baths and signed up on September 16th. He had followed the example of his brother George who signed up on July 16th, George joined the London regiment in the Kensington Rifles, the 13th Battalion of the 1st Regiment. They filled up the first regiment battalions by the time Arthur joined so he was in the 2nd, or reserve regiment. Two other Great Uncles, Charles and John Hames, went from Bullwell, in Derbyshire where they lived and worked, to Derby and signed on for the 1st Battalion of the Sherwood Foresters, and were given consecutive regimental numbers. Another Great Uncle, Fredrick Britton decided that the life of a miner might be less exciting than a soldier and he signed up in Nottingham and he joined the 7th Battalion of the Sherwoods, his cousin Mark also decided that mining wasn’t as cool as soldiering, mining was a ‘protected’ employment, England needed coal, so both could have stayed at home. My grandmother Alice’s brother William lived in Hucknall, he was also a miner, he signed up and joined the 10th Battalion. My paternal Grandfather, Jim, with two kids already stayed behind and dug coal.

So how goes the war at this point? This was all supposed to over by Christmas and the Germans nearly made that happen. French and the BEF, with Haig in charge of half of it, arrived in France on the 14th of August and marched up to Belgium taking positions to the left of the French 5th Army. Haig continues to bitch about John French’s decisions. The Germans sweep through Belgium and catch the Brits unprepared; they first fight each other at Mons on the 23rd. Up to this point the Germans and the British – ruled by King and Kaiser both Grandsons of Victoria – have been allies, the Prussians saved Wellington at Waterloo. The Germans were known to most Brits as waiters, for some bizarre reason most London restaurants in the Edwardian era had German trained waiters. The immediate impact of the war was all the waiters leaving to go home to Germany and sign up to fight the French.

The BEF under Sir John keep getting caught between trying to hold a line and then being forced to retreat when the French army on its flank suddenly pulls back. At one point Haig and his staff think they will be attacked, he led his staff into the street, revolvers drawn, promising to “sell our lives dearly” and the fighting caused him to send an exaggerated report to Sir John, which caused French to panic. At this point they start a fighting reteat to the Marne to meet up with Joffre and the French Army and Sir John is planning to skedaddle to the coast to save the BEF. Kitchener arrives and basically tells him to man up and go attack the Germans.

The Germans and the BEF keep trying to outflank each other in a race for the sea. Kaiser ‘Bill’ referred to the small British Army and their interference in their great plan to sweep around and capture Paris as “Sir John French’s contemptible little army”. The ‘Old Contemptibles’ were a professional army, even though Haig didn’t think to provide the BEF with many machine guns the rate of fire was such that the Germans held off attacking the beleaguered and outnumbered British troops at the Yser, as they thought they did indeed have machine guns and the Germans absolutely understood their power. The Belgian King Albert, unusually for the combatants not related to Victoria but married to a member of the German royal Family, took the decision to open the dyke gates and flood the drained land sealing off the coast route so the first battle of Ypres took place.

Haig made his reputation here as the BEF was outnumbered heavily, not just with troops but with artillery (I wonder why?) They managed to hold on to Ypres. When the Germans could have pushed through as the BEF was on its last legs the German advance stopped and by 8th November, Falkenhayn had accepted that the coastal advance had failed and that taking Ypres was impossible and they decided to dig in. Haig’s big lesson from this was to not give up, even with huge losses.

From 21 to 23 October, German reservists had made mass attacks at Langemarck, with losses of up to seventy per cent. Industrial warfare between mass armies had been indecisive; troops could only move forward over heaps of dead. Both sides were exhausted by these efforts; German casualties around Ypres had reached about 80,000 men and BEF losses, August – 30 November, were 89,964. The Belgian army had been reduced by half and the French had lost 385,000 men by September. Both the allies and the Germans were exhausted, short of ammunition and suffering from collapses in morale, with some infantry units refusing orders.

Kitchener realized it would not be over by Xmas and so had pushed for mass recruitment of volunteers to be trained in a new army to replace all the lost professionals of the BEF. Haig’s 1st Corps had been reduced from 18,000 men to just under 3,000 by 12 November. 4 Days later Haig gets promoted to full General.

Charles and John Hames had arrived in France with the Sherwood Foresters a week earlier. Arthur’s brother George in the Kensington Rifles arrived in France a week after the Sherwoods and went straight into the line for the Battle of the Aisne and found themselves fighting for their lives almost as soon as their feet touch French soil. They gradually retreated from prepared positions to the south of Mons losing a third of their men. They then moved to Estaire on the Lys. It was next the turn of the Sherwoods on the 18th of December went into Battle at Neuve Chapelle.

Early 1915 and Haig is promoted to be in command of the First Army so all my relatives had the dubious pleasure of serving under him and many of them directly under General Hubert Gough. When everyone signed up to go to war, some actually went pretty quickly if their regiment was a standing unit with experienced troops in it. Some were in Reserve units, sent to be trained and then went to war. My Great Uncle Mark joined the 4th Battalion of the Lincolnshire Regiment, technically a reserve unit. They lined up next to George Harris’s 13th Londons for the Battle of Aubers Ridge. They were drawn up at night ahead of the attack. At 5.00 am the bombardment opens, 5.30am the Kensingtons move out into the narrow no-man’s land which is down to 100 yds across, they can see German bayonets over the top of the parapet. At 5.40 a mine is blown and the lead companies of the Kensingtons rush to occupy the craters, move forward to capture Delangre Farm and form a defensive flank. 6.10 am the Sherwood Foresters are sent in to support the attack, as are Mark Britton’s Lincolnshires who cross by the craters of the mine. There are 3 pockets of British troops but not in contact with each other and are under ”pressure’ ie the Germans are shelling the shit out of them. Haig keeps passing orders down for Rawlinson, who is leading 24th and 25th Brigade, to push on the attack. He orders a new bayonet attack at 8.00PM. Some troops have been in the German lines since 5.30 AM. He realizes it is impossible due to the chaos in the support trenches to get fresh troops up. Finally at 3.00 am the last few Kensingtons retreat back to the British lines, the last of the original attacking forces to hang on.

George was killed in that battle on the 9th of May. He like many others was noted as killed in the War Diary but they never located his body. He is memorialized at the Ploogsteert Memorial. Mark lost an eye but survived and came home and other than his glass eye was an amiable and chattier version of our more taciturn Granddad Jim. The attack was less successful than Neuve Chapelle as the forty-minute bombardment (not enough artillery) was over a wider front and against stronger defenses; Haig was still focused on winning a decisive victory by capturing key ground, rather than amassing firepower to inflict maximum damage on the Germans.

I found Arthur’s Battalion’s War Diaries and then those of the other Great Uncles and Second Cousins. They are available on-line at the National Archive. Each British Army unit kept a diary during the war. The commanding officer or adjutant wrote, often in crappy pencil, sometimes in fountain pen, a brief note describing the events of the day. It gives the location and then an entry. They range from “Quiet day, some shelling, Lieutenant Graves killed, 2 ORs killed, 6 wounded” a quick exercise in understatement, to long descriptions of actions with appendix maps and honor rolls – the names of every soldier who took part in a particular action. They reflect the personality of the writer, they also reflect the circumstances. Often written in the mud, rain, under fire, constant artillery shelling, snipers killing the clumsy or during the boring but pleasant tedium of the reserve areas. The Army worked out that keeping men in the mud-filled hell that front line trenches were reduced to, sometimes under non-stop shelling, for longer than 3 days was just a path to mutiny or wholesale surrender. So the British Tommy learned to endure the 3 days, keeping their heads down, avoiding exposure to the shrapnel, living on tinned meat and jam and the occasional warm tea cooked over paraffin lamps. Arthur described bringing up rations from the communication trench leading to the rear and stamping hard on the duckboards, hoping they would break and give him a ‘Blighty’ broken leg, a wound bad enough to require hospitalization in England but not life changing.

The officers though were told to avoid complacency or malingering by sending out patrols every night into No Man’s Land, the disputed charnel house that was the strip of mud separating the German front line from the British one. Sometimes the distance was down to 50 yards, in other places 600 yards. Featureless collections of water filled mud craters with thickets of barbed wire channeling the unaware into the crossed fields of fire of the defending machine guns. Scrambling over the top at night armed with clubs, knives, grenades and pistols, they tried to get to the German lines unspotted, cause some carnage, grab some prisoners and come back unscathed. Sometimes they did, sometimes they didn’t, sometimes the Germans decided to do the same. This description from the Linconshire Regiment War History describes these periods: “suffered many casualties from artillery, trench mortar and rifle and machine-gun fire, for the thirty-five days in the trenches cost the battalion eight officers 1 and one hundred and twenty-five other ranks. These casualties were chiefly caused in the support and reserve lines and during reliefs. The front line suffered only from trench-mortars, and perpetual rifle grenade-fire.” One major difference between the two lines of trenches is that the Germans consciously built defensive positions as they had captured land in France and Belgium so were happy to defend it, while they tried to win the war in the East against the Russians which was more open. To defend their lines, they built reinforced concrete bunkers, deep underground, fitted with ventilation and kitchens. Linked by tunnels and interconnecting trenches and machine gun posts. The British, meanwhile, were only going to be there temporarily as they would soon be completing one of Haig’s bug push and driving Jerry back home! So the British trenches were wooden reinforcing with sandbags and duckboards. Fred Britton’s 7th Robin Hood Battalion of the Sherwoods arrived in France on the 28th Of February and arrived at the Front near Ploogsteert. They spent the next months training, marching, practicing attacking trenches. They saw action attacking the German strong point the Hohenzollern Redoubt on October 13th during the Battle of Loos. Captain Vickers of the Robins won the VC in action on the 14th holding out against German counter attacks, and unusually, survived to receive it.

The Battle of Loos is a failure to break through even though Haig uses Chlorine gas on the Germans. Haig claims success for his part and manages to place the blame on French for the failure to take advantage of the initial success. As I said he didn’t like John French and undermined him directly with the King who he was chums with. He succeeds him in December 1915 and becomes Commander in Chief and his fellow conspirator Wully Robinson becomes Chief of the Imperial General Staff in London, reporting directly to the Cabinet of Lloyd George. 1916 is mainly a precursor to the biggest push of all, the Battle of the Somme.

Haig attended church service each week with George Duncan, who had great influence over him. Haig saw himself as God’s servant and was keen to have clergymen sent out whose sermons would remind the men that the war dead were martyrs in a just cause. Haig’s other guiding principal was that Germany was nearly done, in 1915, in 1916 and again in 1917 he was sure that the Germans were exhausted, that they were running out of men and running out of the will to fight. In spring of 1916 Haig thought that the Germans had already had plenty of “wearing out”, that a decisive victory was possible in 1916 and urged Robertson to recruit more cavalry. In March of 1916 Haig’s preference was to regain control of the Belgian coast by attacking in Flanders, to bring the coast and the naval bases at Bruges, Zeebrugge and Ostend. He used the same plan again in 1917, you can’t say the man didn’t have sticking power.

Meanwhile William Wilson, Fred Britton, John and Charlie Hames are part of a minor action referred to as the Bluffs. Bill Wilson’s 1st Battalion Sherwood Foresters relieve the 7th Lincs, Mark Britton’s old unit in trenches at the Bluff, near the Comines canal south of Ypres. On February 14th 1916 they got shelled heavily as a precursor to an attack they knew is coming. The Germans come into the decimated front-line trenches with bombs and the front line is lost. They are ordered to counterattack. That is not successful so they are asked to do it again, with some reinforcements from other units. They are moved to the reserve trenches but ordered to help out with another counterattack on the 15 and 16th and finally the “remnants” of the 10th Battalion was relieved. Casualties of this minor action were: “Killed: Captain Goodall, Lieut Ramsay and 2Lt Milward; wounded Capt Fisher, Lt Cuckow, Lt Meads, Lt Abbots, 2Lt Thurlow, Lt Daniel, 2Lt Davis; Missing Capt Carylon, Lt Knox-Shaw, Lt Tollemache, 2LT E.Ebery, 2Lt Chandler, 2Lt Melville. Other Ranks kille 23, Missing (blown to nothing in the trenches)163, Wounded 148 of which 31 remained at duty.”

There was a detailed plan for recapturing the lost ground which took place on the 2nd of March, the Sherwoods were mainly in support, acting as bearers and bringing up grenades and ammunition. The attack was successful. The support action saw another two officers killed, one wounded, 17 other ranks killed, 76 wounded and 3 missing, one of which was my Great Uncle Bill Wilson. His name is on the Menin Gate in Ypres.

The Robins are shuffling back and forwards between billets and former French trenches near Mont St Eloi. The Germans, like the British, tunnel under the trenches and set off several mines as a precursor to attack. Fred Britton is killed on 16th April when the mine goes up. They obviously never find his body and he is named in the Ploogsteert Memorial too.

Meanwhile the Germans are grinding the French at Verdun so the French command under Joffre want a joint British French attack in the Sommer. The idea being to divert German troops away from Verdun in the south and give some respite to the beleaguered garrisons there. Haig now decides he needs more build up and wants to put this back until August. When told of this Joffre shouted at Haig that “the French Army would cease to exist” and had to be calmed down with “liberal doses of 1840 brandy”.

Much has been written of the Battle of the Somme, suffice it to say that bravery and lots of clever rehearsing do not make up for the stupidity of having massed infantry try and storm very deep, well protected defensive positions, regardless of the amount of artillery shells you throw ahead of the men. The German positions on the Somme had been steadily reinforced since January 1915, so in a way they had 15 months to prepare. Barbed wire obstacles had been enlarged from one belt 5–10 yards wide to two, 30 yards wide and about 15 yards apart. Double and triple thickness wire was used and laid 3–5 feet high. The front line had been increased from one trench line to a position of three lines 150–200 yards apart. The Germans had not only watched the British use the same tactic over and over again, they learned from it and so the first trench was very lightly occupied by sentry groups, the second for the bulk of the front-line garrison and the third trench for local reserves. The trenches were zig-zag and had sentry-posts in concrete recesses built into the parapet. Dugouts had been deepened from 6–9 feet to 20–30 feet, often 50 yards apart and large enough for 25 men. An intermediate line of strongpoints about 1,000 yards behind the front line was also built. Communication trenches ran back to the reserve line, renamed the second position, which was as well-built and wired as the first position. The second position was beyond the range of Allied field artillery, to force an attacker to stop and move field artillery forward before assaulting the position. So they had a well-developed tactic of letting the Brits and the French shell the crap out of the front line trenches, while they hunkered down, when the waves of Commonwealth troops ran to take the front line trend they were shelled with shrapnel and machine gunned, especially in the choke points in the gaps in barbed wire. When the Allies had worn themselves out on the fighting to get through the first 2 lines the Germans then threw in their shock troops to counterattack. The Germans were ready, the date and location of the British offensive had been betrayed to German interrogators by two politically disgruntled soldiers several weeks in advance. The German military accordingly undertook significant defensive preparatory work on the British section of the Somme. The British unsurprisingly had the worst of it, as in the first day was the worst in the history of the British Army, with 57,470 casualties, 19,240 of whom were killed.

After basically non-stop fighting from July 1st to the last part of the battle for Ancre the British, Canadian, Australian, Indian, South African, New Zealand, and French had advanced about 6 miles north east on the Somme, along a front of 16 miles at a cost of 432,000 British and Commonwealth killed, wounded and missing and about 200,000 French casualties, against between 465,181 and 600,000 German casualties. German records are fragmented and some did not survive the second world war, hence the uncertainty. Regardless of which number is used a vastly costly and ultimately pointless exercise in killing most of a generation.

What was learned? Firstly, you need lots of artillery to try and kill as many Germans as possible, you also saw the need for tunneling and mines which solved the problem of the German defenses by blowing great big holes in the ground under the defensive positions. But Haig felt it was all worth it, all the death and destruction, as it was a war of attrition, and the Germans were running out of men and munitions and just about to give up. Haig had as his Intelligence Chief Brigadier General John Charteris. He had been appointed as ADC to Haig when he first went to France in 1914. He had no intelligence background but was young, a “good chap” and spoke French and German. Haig liked him. Charteris was brash, untidy, and liked to start the day with a brandy and soda. He was a sort of licensed jester (known as “The Principal Boy” due to his rapid promotion from Captain amidst Haig’s staid inner circle. He is often quoted as the source for the saying ‘Military Intelligence is a contradiction in terms’. The dour chaplain Duncan remarked how Charteris’ “vitality and loud-mouthed exuberance” made him universally unpopular, except with Haig.

The biggest problem with Charteris was that he filtered any reports to only show Haig what he wanted to hear. He was constantly feeding him reports from German prisoners that they were on their last legs and ready to give up.

On 1 January 1917, Haig was made a Field Marshall. The King (George V) wrote him a handwritten note ending: “I hope you will look upon this as a New Year’s gift from myself and the country”. Haig decides he can end the war by pushing through the German lines, sweep through with cavalry capturing the rail hub of Roulers and then taking the ports of Zeebrugge and Ostend and stop the U-Boats from starving England out. The fact that the U-boats were mainly based in Germany was a minor inconvenience. The place they decided to do this was the Ypres Salient, to not just capture the various ridges overlooking battered Ypres but the open ground beyond was the key. There were a couple of major obstacles. Firstly, the Germans decided in late 2016 to shorten their defensive line and gave up land to move back to the Hindenburg Line as it was dubbed. The new line was constructed with ferroconcrete and built on prior lessons about crossing fields of fire, bunkers and strong points. They massed machine guns and artillery.

5th of February my grandfather Arthur and the 2nd/10th London Regiment, The Hackney Rifles arrived in France and were moved to near Arras. The Hames brothers and the 1st Battalion of the Sherwood Foresters are in support trenches in the Cambrin sector. The preparation for the big push continues.

Haig is going to use tanks to support the upcoming attacks. 4th of May Arthur’s unit is moved to Favreuil and then into the reserve line on the 5th near Lagnicourt-Marcel in the Bullecourt sector of the attack. Spent 7 days in line and then relieved and back to Favreuil. Moved up to Bihucourt, then Mory and finally on the 22nd back into the line relieving 2/9th at Ecoust St Mien and taking over at Bullecourt on the 27th. Charles and John Hames move up to Ypres and at the end of May are at the Lille Gate of the ramparts of Lille. The Hackney Rifles and Arthur are on to Bullecourt on June 7th. This day the British blew up 19 of the 21 mines they had dug below the Messines Ridge and the 3rd Battle of Ypres or Passchendaele as it commonly called started.

The 14th June 3 officers and 60 men of the Hackneys raided German front line. Captured 2 prisoners, brought a machine gun back and destroyed two others. One officer G.W.Hills and 4 OR killed, the other two officers wounded together with 38 OR, 7 missing. Later that day they were relieved by Gordon Highlanders and went back to Mory. 26th June the 1st Battalion Sherwoods are moved to relieve the 2nd Middlesex in trenches outside Ypres at West Lane. They are shelled constantly with 77mm artillery from the Germans. On the morning of the 30th, ‘glorious weather’, rifle grenades killed 4 men including Charlie Hames. He is buried in Dickebusch New Military Cemetery Extension, just outside Ypres to the south west.

The ongoing battle towards the village of Passchendaele continued through the summer, Arthur’s Battalion are involved near St Julien but everything grinds to a halt as the unseasonable rain makes it a quagmire. The land there is normally drained by various canals and dykes but they have been blown to pieces in the preceding 3 years so it becomes a morass. John Hames’ Sherwoods complete a raid on the German trenches on the night of 3rd July but that’s just a precurser to their action in the Battle for Pilckem Ridge on the 31st July.

Haig’s great idea to use tanks has hit a basic problem, they sink into the mud. The Tank commanders have given a map to Charteris showing where they could possibly operate and it’s a large map with a lot of areas crossed off as being impassable for tanks. Charteris decides not to show Haig on the grounds it would only depress him.

The Hackney Rifles rotate between reserve trenches and camp, training and relief work in regular rotation. September rolls around and they are to be part of the Battle of the Menin Road Ridge. The War Diary shows they went into Poelcapelle sector into trenches at Mon de Hibou. Shelled heavily 22-24th especially between Quebec and Strop Farm. Relieved 24th and split between Juliet Farm and California Drive, the Battalion HQ was at Cheddar Villa. Cheddar Villa exists to this day. It’s the remnants of concrete bunker, partly hidden behind a modern boring farm building just outside St Julien. The Diary continues” California Drive bombed by aircraft on the 25th and 4 killed and 22 wounded. Companies moved up to Front line at St Julien, Winnipeg Rd and Custer Houses”. My brother and I walked up the hill from St Julien to Winnipeg Rd and along the ridge to where the Custer Houses was, we walked past the German windmill of death, “Todesmühle”.

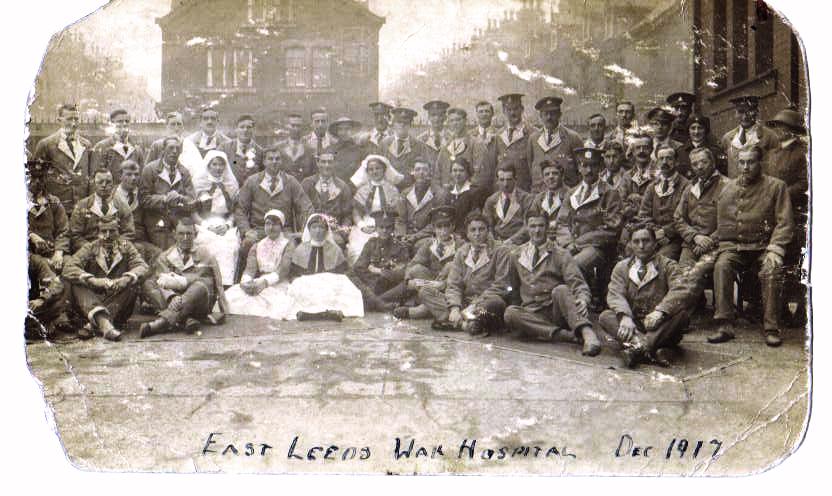

Arthur was gassed on the 26th. Following morning pulled back to Dambre Camp where the Battalion continued to be bombed by Germans. Arthur was evacuated back to England and spent 6 months in hospital in Leeds.

Meanwhile Hames’ Sherwood Foresters were out of the line recovering. On the 1st of October they tallied up their losses in the war to that point as 92 officers, 2817 other ranks, killed wounded or missing. On the 3rd of November while the Battalion was holding the line near Ypres when they were visited by two “officers of the American Army, Lieut. H.E.Hutchins and Lieut. Pullen arrived and were attached to the B Company”. Now north of Passchendaele they continue to be part of Haig’s final end to the 3rd Battle of Ypres. What did this cost? British losses of 275,000 and German casualties at just under 200,000 seem to be consensus. In his memoirs in 1938, Lloyd George wrote, “Passchendaele was indeed one of the greatest disasters of the war … No soldier of any intelligence now defends this senseless campaign ..” Haig however defended it rigorously after the war.

In April of 1918 when the Germans, re-fitted with men from the Eastern Front, after the defeat and surrender of Imperial Russia, launched their big spring offensive. The British High Command decided that the mess that was the ridges around St Julien, Zonnebeke and Passchendaele were too difficult to defend and they retreated to a defensible line near Ypres. They gave up in two days what took from June 7th to November 18th just months earlier to capture.

That spring the last surviving member of my extended family was still with the 1st Battalion of Sherwood Foresters. They were transferred from the Ypres salient at the end of March to the Somme and defended the River Somme outside St Omer in a village called St Christe. The enemy tried to cross the river on the 23rd in the evening, over the partially demolished bridge, they raided again the next day but on the 25th the troops on their right withdrew under orders leaving their flank ‘up in the air’. They were then surrounded by the attacking Germans and decided to fight a retreat through Misery and defend a line at Estrees. In the fighting retreat John Hames luck finally ran out and he was killed. Due to the nature of the retreat the place where soldiers fell were not marked so John is remembered in the Pozzieres Memorial. He managed to survive almost 4 years of which 3 were in the trenches in active combat.

The Germans kept up several offensives through the Somme and nearly made it to Amiens and the railhead linking the British and the coast and Haig was in trouble, Petain in charge of the French Army was worried he would have to defend Paris. But in the end the German supply lines got too long and stretched out and the rout of the British and French became a sustained defense and then transitioned to counter attacks as the German troops were just exhausted. Unsurprisingly they ended up retiring from most of the ground they captured, without major disruption of the Allied supply points or Paris. Haig then attacked and using what they only took 4 years to learn: combined tanks and infantry, quick unit-based attacks coordinated with brief artillery bombardments that didn’t carve the land up into a quagmire. The 100 Day offensive battered the disenchanted German infantry and finally broke through the Hindenburg Line. As the German troops started to mutiny, food ran out in the homeland and the communist elements in the Navy were in open rebellion the Germans started to negotiate a surrender. All through October the allied troops kept pushing the retreating German Army back while the French negotiated as hard a surrender as they felt they had been forced to agree to at the end of the Franco Prussian War. In the process they laid the groundwork for the feelings of anger, betrayal and injustice to fuel the next world war and the economic terms to ensure it would enable the extremist Nazi party to take power and almost guarantee it exploded into reality just 20 years later.

The First World War brought about the end of the era of empires, colonial or land based, two disappeared immediately, the Russian empire of the Romanovs and the Austrian empire of the Habsburgs. The Turkish empire of the Ottomans finished its long decline and fall not long after their defeat. France and Britain were emotionally and financially bankrupted by the carnage and the United States was probably the only overall winner. The British Empire had seen its children slaughtered for King and Empire under at times terrible British leadership and decisions and it created a sense of self-determination being not just a reasonable expectation but an imperative that took another 20 years to fulfill. It was also the end of an era of assuming that the Kings and Kaisers knew best. When Britain went to war again, reluctantly, in 1939, again to stop the Hun, it may have been dressed up as fighting for King and Country but it was fighting for each other, the Country part. In 1914 Fred and Mark Britton, Charles and John Hames, William Wilson, Dennis Baker, George and his brother Arthur Harris, my grandfather, all volunteered to go to war, happily, for God, King and Country together with just under 9 million men who served in the military. The same fervour gripped Germany, Austria, Hungary, Russia, Italy, Belgium, Rumania, Japan and France, an estimated total of 60 million men joined and served in the various branches of the military, a number not seen since.